Thesis: Development of musical thinking of junior schoolchildren in music lessons. Musical thinking and its functions

M. KUSHNIR

COMPLEX METHODOLOGY

DEVELOPMENT OF MUSICAL THINKING

Theoretical foundations of the complex methodology

The main task of upbringing and education in children's music schools is to prepare the student for active creative activity. Existing teaching traditions have a number of negative aspects. One of them, a very significant one, is that people who graduate from school sometimes not only do not become professionals, but even music lovers. This means that the school does not develop in students the ability to understand musical language, think in musical images, and does not lay the foundations of musical thinking. Regardless of whether a school graduate becomes a professional musician or not, the initial stage of training at a music school should be aimed at developing musical thinking. This is the most important goal of music pedagogy.

The methodology we have developed, aimed at achieving this goal, is based on principles whose interaction in the educational process is complex. That is why it is called “Comprehensive methodology for the development of musical thinking.”

Its creation was dictated by the need to educate a creatively active personality. The development of scientifically based methods for the formation of musical thinking is associated with the urgent need to rethink various traditional types and forms of training.

In this article we would like to dwell on some didactic principles underlying the complex methodology: the principle of integrity, the principle of active activity, the principle of creativity and the principle of mental hearing.

Selection principle of integrity due to the very nature of the object of study - a work of musical art and all its components. In music there is no separate melody, harmony, rhythm, etc. The work is perceived only in the totality of all means of expression. Therefore, the integrity of the object being studied is not only the starting point, but also the final goal, the result of the entire learning process. The didactic principle of integrity dictates first of all the direction of the learning process from the whole to the particular, and only then from the particular to the whole. These two directions of the learning process form a dialectical unity. Practice shows that with this approach, what is important is not the number of phenomena being studied, but finding connections between them, and through this, determining the meaning of the whole (not just knowing all the intervals, but understanding the system of intervals as expressive elements of the melody, chords; a preliminary analysis of the piece should be carried out not with each hand separately, but with both hands in the qualitative certainty of all the connections of the textured whole; in order to have a holistic idea of the style of Bach’s music, the teacher must orient students not to one or two of his pieces, but to a group of pieces that are most characteristic of the composer’s work, etc. P.).

The second principle of the complex methodology is active principle related to all four sides music training– listening, performing, analyzing and composing. There is no doubt that each form of work requires its own relationship between these aspects, and at the same time, all types of educational activities require their active combination. For example, ordinary listening to music is a very complex process. Firstly, with active listening, a person, to one degree or another, identifies himself with the performer, mentally playing along with him. Secondly, active listening also includes the factor of composition, or more precisely, “additional composition” or “addition”: the listener, as it were, foresees, anticipates the further development of music (in psychology this is called anticipation). Such anticipation usually occurs when listening to a piece for the first time. When listening again, the listener’s “advanced composition” turns into “advanced performance.” Thus, the overall complex of activity does not decrease with repeated listening. Third, the factor of active listening is analysis. In this case, the activity of listening is expressed in the analysis of the types of activity of the performer: such as, say, the pedal, tempo, movements of the pianist’s hands in passages, the violinist’s bow, etc. The objects of analysis are also the associations evoked by the sound of the work - spatio-temporal, visual , literary, etc. But, of course, the analysis of musical structures and the connections between them comes to the fore in importance. The degree of differentiation of perception is directly dependent on the level of knowledge, including special musical knowledge. Thus, the depth of music perception depends on the activity of all three factors combined during listening - performance, composition and analysis.

In a similar way, we understand the manifestations of the principle of active activity in relation to other aspects of musical education - performance, analysis, composing music. Each of these forms of work must be combined with the other three in order for training to truly develop musical thinking.

The third principle of the complex methodology is principle of creativity. The concept of creativity includes a constant active search for something new and original. As in art in general, in music creativity is the creation of a work of art. Composing music can, in turn, be creative or instructive, that is, directly related to the learning process.

In the educational process, creativity is a mandatory element when studying any topic in any subject of the theoretical cycle, be it solfeggio, music theory, harmony, analysis or polyphony. Thus, in the solfeggio course, creative work is necessary for students already because only “verbal” acquaintance with certain theoretical concepts does not indicate the very fact of their musical comprehension, while the experience of composing does not pass without a trace either for memory in general or for musical thinking in particular.

In a music school, the practice of composing simple piano pieces, usually in a simple homophonic-harmonic texture, can be successfully used. Somewhat later, it is permissible to use polyphonic texture techniques in the composition. Elements of the composition can be used when studying the corresponding sections of programs in both solfeggio and music theory and analysis. At the same time, the essay must clearly correspond to the means of expression, techniques, and forms being studied. For example, working on a two-voice dictation will be greatly assisted by students composing two-voice exercises.

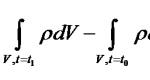

The fourth principle of our methodology is the principle of mental hearing. He has essentially been known for a very long time. Various authors at different times paid attention to its individual aspects: these are, for example, internal intonation, internal hearing, musical fantasy (according to Korsakov), learning a piece by heart from a musical text without playing (I. Hoffman), etc. About a hundred years ago, a prominent German piano teacher in his book “Individual Piano Technique Based on Sound-Creative Will” proposed to base the development of creative abilities and artistic thinking of the student on the so-called “prodigy complex”: the sequence of actions when studying a piece of music - “see - hear” - I’m playing.” (He describes musical ability as an example of such a path.) This is the path from auditory representation(“I see - I hear”) through motor skills to sound (“I play”). This sequence is a logically constructed integral system of perception and reproduction of the musical text of musical works. Schematically, Martinsen presents this system as follows:

https://pandia.ru/text/78/515/images/image003_190.gif" width="226" height="63">  Discourse" href="/text/category/diskurs/" rel="bookmark">discursive constructions.

Discourse" href="/text/category/diskurs/" rel="bookmark">discursive constructions.

Mental hearing as a function of the “RAM block” is without a doubt the basis of all types of practical musical activity. Moreover, the activity of the RAM block at the level of mental hearing is one of the main evaluation criteria musical abilities or even the degree of musical talent.

In other words, the qualitative and quantitative aspects of mental hearing largely determine both the degree of development of musical abilities and the level of professional skill. The quantitative side is characterized by the time during which consciousness operates with mental musical structures or images. There is data indicating the possibility of almost continuous operation of the musical component of the musician’s RAM block, which, in general, ensures his usual professional level. This can be judged by the following analogy: internal (verbal) speech in the same block continues almost continuously (everyone can easily see this), but this only maintains the level of our intelligence.

The qualitative side of mental hearing is manifested in the degree of hearing activity, in the brightness of ideas, and the ability to operate with them. This can be an involuntary repetition of a motive (“a melody has become attached”) and a phenomenal phenomenon - the artistic and creative ability to mentally reproduce musical structures, up to the simultaneous “timeless” mental hearing of the sound structure of an entire work (Mozart had this ability).

The development of methods and techniques for the development of mental hearing, after careful experimental testing, could become an effective tool in the pedagogical process in both professional and mass music education.

So, the aspects of the complex methodology we are considering - the principle of integrity, the principle of active activity, the principle of creativity and the principle of mental hearing - in a specific educational process are realized in interaction and are carried out through each other. Thus, the complex methodology is holistic in itself.

Practical implementation of a complex methodology.

We have been conducting experimental testing of the complex methodology for over five years in parallel with research into theoretical premises. The practical base was Children's Music School No. 2 in Tambov.

The “introduction” of a complex methodology into educational and pedagogical practice is carried out entirely within the framework of existing curricula and programs. Therefore, the practical implementation of the methodology is carried out in the form of partial changes in individual methods of teaching subjects of the musical-theoretical cycle with some re-emphasis on a number of provisions and requirements of the programs.

One of the essential elements of the general pedagogical process is an individual approach to teaching: on the one hand, this is the individual approach of the teacher to the student, on the other, the individual attitude of the teacher to the forms and methods of teaching. It follows that each teacher must creatively embody the principles and provisions common to all in individualized techniques. What practical recommendations follow from theoretical foundations complex methodology?

First of all, it seems necessary to us to create within the framework of each academic discipline such forms of work that would help reorient the teacher towards solving the main task - the development of musical thinking in students based on conscious internal manipulation of the structures of musical art (hearing musical structures, their variations and composition). Consequently, the goal of this technique is to appropriately rearrange the functioning of each student’s RAM block. Class work should be conducted in such a way that the student consciously tried to solve the problems set by the teacher.

Let's consider the practical implementation of the principle of mental hearing.

It is necessary to take into account that our consciousness contains as a mandatory internal speech layer, i.e. verbal dialogue. There may be more such layers - command of a second language, mental play of chess, internal handling of images of the plastic arts. A similar layer, which is of utmost importance for the development of musical thinking, is the internal hearing of music. If internal dialogue or external communication becomes the dominant feature of the operational field, then internal hearing of music (like any other secondary layer) sounds like subtext, fading into the background.

If a teacher sets a student the task of mentally hearing any musical structure, he should start from a comparison with the mental sound of the verbal structure (similar to the internal pronunciation of a word, the student imagines the sound of the musical structure).

What and how can and should “sound” in the mind of a schoolchild studying music? To answer this question, let’s turn directly to practice.

The core point in the solfeggio course in experimental classes is the study of both individual musical works and cycles. These works are songs, piano pieces, romances, choruses. Specific material: in grades 1-2 - children's songs from the curriculum, plays from the "School of Piano Playing" ed. and "Children's Album" by Tchaikovsky; in grades 3-4 - revolutionary songs, “Children's Album” by Tchaikovsky, “Little Preludes and Fugues”, two-part inventions by Bach; in grades 5-(6-7) - two- and three-voice inventions by Bach, preludes and fugues from volume I of Bach's art theory, songs by Schubert, romances by Glinka, sonatas by Beethoven, piano miniatures by Schubert and Chopin, Russian folk songs, cycle of plays "Children's Music" » Prokofiev.

As a rule, each student should see the notes of the work being studied during class lessons. And we teach children to follow the music from the musical text, starting this work already in the second quarter of the first grade (say, from listening to pieces from the “Piano School”). As a result, by the fifth grade, students develop the ability to follow the text of Beethoven’s sonatas, symphonies of Beethoven and Schubert (by the senior year, partially even using scores).

The development of the ability to follow the music being performed from the notes from the very first steps of learning is combined with the skill of reading music text and its reproduction. The student goes through the following stages of mastering musical material: mental reproduction of music by heart; reading notes with maximum approximation of the mental sound to the real one; performing themes of works on the piano by heart; alternating mental and real performance. Repeated listening to a piece while simultaneously following the notes leads to the effect of mentally hearing the text without its actual sound at that moment (from “I really hear - I follow” to “I see - I really hear”).

The most important condition for adequately hearing a text is its in-depth and systematic analysis. The level of analysis is largely determined by the teacher’s preparation for the lesson. Image, texture, chords, mode-tonal relationships, form, development techniques, etc. - all these elements of holistic analysis are introduced into the learning process from the first grade. And even if not right away, this approach to solving the problem gives good results, you just need to show persistence and patience.

In the formation of a student’s block of operative memory, the quantitative factor also plays a significant role: a large volume of learned works has a beneficial effect on the development of long-term memory, improves associative connections, and expands the students’ thesaurus. As the experiment shows, the number of works that a student of average ability can learn during five years of school is approximately the following: 10 children's songs, 5 pieces from the “School of Piano Playing,” 8 “Little Preludes” by Bach, 10 revolutionary songs, several pieces of Tchaikovsky’s “Children’s Album”, the first movement from Beethoven’s 8th sonata (in this case, listening with following the notes and mental reproduction, since performing the sonata is still practically inaccessible to a fifth-grade student).

The work studied in the solfeggio lesson also serves as illustrative material. If, for example, by curriculum In this lesson, students learn a new key, then they should select works in this key.

Simultaneously with the formation of students’ mental hearing through the analysis of individual expressive means of works, there is a process of step-by-step introduction of various elements of the structure of the musical language into the block of operational information. To this end, it is practically possible to reorient all types of work in solfeggio lessons from formal consideration to the level of mental hearing. Thus, when working on intonation exercises, the student is offered a specific program of action:

Task. Sing tritones with resolution in F minor.

1. Mental tuning in tonality (“mentally you must play the tonic triad, the harmonic scale of F minor and hear - mentally! - everything you play”).

2. Theoretical solution of the problem (“speculatively construct all four tritones and solve them. Imagine them on the keyboard or on the staff. You must accompany your mental solution with three rows of notations, “inscriptions”: 1) steps; 2) notes; 3) interval. The following chain should appear in your mind: the first tritone - from the VII increased degree of the harmonic F minor to its IV degree. These will be the sounds “E-bekar” - “B-flat”, the interval is a diminished fifth. It is resolved in steps I – III, “F – A-flat”, this will be a minor third. Second tritone “... etc.).

3. Mentally hearing all four tritones with resolution (“go back to the tuning, mentally repeat the tonic. Listen carefully to the first tritone with resolution, first melodically from bottom to top, then harmonically. Then the second tritone, third, fourth”).

4. The solution to this problem is completed by singing all four tritones out loud, followed by resolution.

Singing a memorized text and singing from sight are perhaps the most common solfeggio techniques. Students sing scales, intervals, chords, one-voice melodies, two- and three-voice exercises. And in class musical literature In addition to the mandatory learning of themes, individual songs, romances, and arias are additionally learned, which ensures an interdisciplinary connection between musical literature and solfeggio. And here mental hearing turns out to be an extremely effective technique that precedes singing out loud.

At the level of children's music schools, this mostly concerns monophony; only the most advanced students can sight-read ("internally hear") developed polyphonic two-voices (such as Bach's inventions) without prior playback and without the help of a piano. But everyone must hear a learned two- or three-voice example. Of course, in the real situation of each specific class, not everything may work out smoothly right away.

The gradual “immersion” of the melody from the sphere of external reproduction, external sound into the sphere of mental hearing occurs according to the following scheme: 1) singing the melody in a choir; 2) alternating singing out loud and mentally hearing in phrases or bars; 3) mental hearing of the entire melody with the exception of “checking points” - the beginning or ending of phrases and sentences; 4) independent reading at an arbitrary pace (at stages 1–3, the teacher sets and maintains a general pace).

“A comprehensive methodology for the development of musical thinking” should be understood not only as a set of didactic principles, but also as a system of interdependent subjects, activities, forms of work, etc. In this regard, the educational side of the learning process seems extremely significant. The student's worldview, focus, ability to sacrifice entertainment for the sake of business - we cultivate all these personality traits in our students from the very first years of study, using all the means available for this. Ultimately, we reap the benefits of being intentional about our work. All other things being equal, the student whose general goal, general attitude is more significant and broader will write the dictation better. If one student in writing a dictation sees only a means to get a grade and get rid of the teacher’s instructions and parents’ edifications, then another sees in the same dictation a step in the development of his thinking.

We must try to organize the work in such a way that the students’ own activities become an instrument of their own education. To do this, for example, you need to diversify your current work with a number of activities that can captivate the children and concentrate their will and attention.

Such events include, first of all, students attending philharmonic concerts. In addition, we invite famous performing musicians to the school and hold thematic lectures and concerts (up to ten per year with the assistance of the piano department of the Institute of Culture). Cool musical and literary evenings (“F. Chaliapin”, “Music and Painting”, etc.) are effective. The guys themselves prepare materials, tell stories, show slides, illustrations, play records, discuss, argue, during breaks they drink tea together with homemade confectionery - a team is born, which is very important for music schools.

And finally, another type of event is competitions that take place annually; they create a kind of peak, a culmination of all work (“long-term perspective”), cause a surge of strength in students, and increase their performance. The educational and educational significance of competitions is difficult to overestimate. Their topics are varied, for example: “For better knowledge of revolutionary songs” (with the participation of a military orchestra); “For better knowledge of the works of Mozart”, “For better knowledge of the works of Chopin, Beethoven, Tchaikovsky”, etc. Thus, we managed to hold the Beethoven competition together with students from other schools and music school students. The program of the Beethoven competition required high school students to know in great detail the 8th, 14th sonatas, 32 variations, the Egmont overture, the Fifth Symphony; 20 fragments from these works (including developments and codes) were given in the "Guessing Game", 25 themes were required to be played by heart with both hands. In addition, knowledge of the composer’s creative path was tested in an oral story competition. Suffice it to say that in the process of preparing for the competition, the students listened to Beethoven’s quartets and concertos (violin, 1st piano), the Third, Fifth, Ninth symphonies, and at least 5-7 sonatas. The students’ work was considerable, but the reward was also great: all the participants in the competition (there were 45 people) seemed to rise to another level in their knowledge, skills, and abilities.

Speaking about the practical implementation of a complex methodology, one can also mean a complex the academic disciplines themselves using common principles and techniques in their work. This applies primarily to the entire theoretical cycle at Children's Music School (solfeggio, musical literature, elective theory and composition). We have already briefly touched upon the problems of complex methodology in solfeggio and composition classes. As for the music theory elective, here too all the principles and activities we described are almost completely applicable. It should be noted that all work relies on a large group of highly works of art, representing the basis of illustrative or analyzed material. In a music theory course, there must be a constant scheme for studying any element of musical language, in which hearing is an obligatory component: studying - mental hearing; theoretical representation – mental hearing – playing the piano; solution - writing - mental listening, etc. Attraction of creativity to all sections of the subject becomes maximum. In each task, in each link of the lesson, there must be either mental hearing, or real reproduction, or improvisation or composition.

The situation is somewhat more complicated with the course of musical literature, since we have recently included this subject in the orbit of a comprehensive methodology. The development of musical thinking when studying musical literature includes, as one of the components, learning a large number of topics. This means that the themes should be played by heart with both hands and listened to mentally. The amount of material learned for schoolchildren of junior and middle age can be very different: for example, the winner of one of the rounds of the competition on Mozart’s works - for knowledge the largest number topics from Mozart's works - a 4th grade student, independently learned 23 topics.

In the course of musical literature, there is experience in students learning complete vocal and piano works. Thus, during a control lesson on musical literature in the 5th grade, in addition to 25 topics defined by the program, each student played by heart one Chopin prelude, one Bach invention and one Schubert song, which had to be sung with words and accompanied. All these works had to be heard in their entirety by heart.

From such a re-emphasis of the musical literature course, a number of provisions can be deduced, the first of which is that one of the main requirements of the subject “musical literature” should be obligation learning complete pieces of music. To do this, at least one work of each composer, a complete example of texture, a complete example of genre, etc., is “stored” into the block of long-term memory of each student. In this and only in this case, it is possible to create in the student’s mind a model of an artistic direction that is motivated and supported by clear associations , stylistics of the composer, specific work. Or, in other words: any verbal description of something will be closed in on itself if it is not based on a specific hearing of the integral structure of the object. In musical literature, this means that all conversations about music without mentally hearing this music do not give the desired effect.

The second point related to the study of musical literature relates to working with musical notation. Both listening to music and analyzing any work should be done only from the musical text, and not by ear. For example, students should be introduced to working with scores as soon as they begin studying orchestral works. Here, apparently, a large number of special anthologies for the study of musical literature will be needed.

In addition, it seems likely to us to introduce listening to music from the first grade of a children's music school as an independent subject that precedes a course in musical literature and is also based on the principles of a comprehensive methodology. A one-hundred-hour three-year course, provided the appropriate notes and books are available, and the classroom is equipped with first-class equipment, can give schoolchildren an artistic and aesthetic boost for life. To experimentally test these provisions, and other possibilities of the complex methodology, such a music listening class is currently being created at our school. Its operation will begin in the very near future.

The next “subject” of the complex is the specialty. The problems that arise here, related to the complex methodology for the development of musical thinking, require further understanding. The principles of the complex methodology and its individual techniques can be encountered much more often in methodological developments the performers themselves, in their practical activities, rather than in the corresponding works of theorists. For example, learning works by heart without an instrument, mentally reproducing a text, reading, and many other techniques of a complex methodology have always been characteristic mainly of performers. And it should be noted that at the present stage, musical thinking is still mostly formed in specialty classes. In this regard, we theorists still have a lot to learn.

Thus, a comprehensive methodology for the development of musical thinking, which we consider as a system of methodological, pedagogical and educational techniques, combines: a) a complex of techniques and activities; b) a complex of forms of classroom and extracurricular work; c) a complex of subjects that use common principles and techniques of a comprehensive methodology.

We believe that, to one degree or another, the principles of the complex methodology can be transferred both upward - to special middle and higher links in the chain of music education, and spread wider - to the system of general music education. But the conversation about this can be continued only if the theoretical provisions of the complex methodology become generally accepted, and the particular aspects of their experimental implementation become part of everyday pedagogical practice.

Second edition, corrected and expanded. Tambov 2006

Musical thinking. Music as the art of intoned meaning. Intonation as a semantic unit of thought processes. Scientific and artistic types of thinking. The most important functions of artistic thinking. Types of musical analysis. Conditions for the development of musical thinking. Qualities of musical thinking, features of external manifestation. Levels of development of musical thinking. Methods for developing musical thinking.

Homo sapiens is a reasonable person. Separating himself with this term from the animal world and primitive savagery, modern man emphasizes his ability to think and places it at the basis of civilization. In various fields of activity, he strives to identify the “intellectual component” and improve the thought processes that underlie it and contribute to its effectiveness. Political thinking, economic thinking, mathematical thinking - such phrases reflect faith in the power of the intellect, multiplied by the specifics of the field of activity. In the field of musical art and music pedagogy, this is musical thinking.

When we listen to a piece of music, we compare the sounds of the melody with each other, distinguish their movement, repetitions, jumps, follow the timbre, rhythmic, harmonic development, feel the modal expressiveness of melodies and intonations, changes in tempo, the beginning and ends of phrases, sentences, parts, compare music from previously heard, we comprehend its content, using all knowledge and experience. At the same time, the universal integrative ability is activated - thinking based on musical language, that is, musical thinking. Try to imagine any person or literary character you know with excellent thinking, such as Sherlock Holmes, and imagine that musical phenomena are not an insoluble mystery for him either. What would he say if he heard Fryderyk Chopin's Nocturne or Franz Liszt's Hungarian Rhapsody? It is likely that he would have been able to determine the era in which the work was written, the style, the genre, a number of features characteristic of the works of certain composers, and, in the end, he would have named the names of the composers, the country and what the music itself was talking about. But without developed musical thinking, which cements and connects all human musical abilities, both complex and elementary, connects them with the general thinking and knowledge of a person, this would be impossible.

What is it musical thinking?

Any thinking is a process, activity, ability - common, universal for all spheres of human existence. The basis of the unity and indivisibility of thinking is the unity of the world, as well as the theoretical and practical activity of man in it. The structural division of a single human thinking, the identification of its individual facets or sides is conditional and only with such a reservation can be recognized as scientifically correct. At the same time, there is a need to distinguish between the essential and the specific, which characterizes the flow of mental processes in different areas of human activity. Musical thinking, like any other type of thinking, combines general and specific features.

There are two most general type thinking: scientific (conceptual) and artistic (figurative). Musical thinking is aimed at understanding two areas in relation to life - music as an art form and musicology as the science of this art form. This allows us to talk about the integration of these two types of thinking in music, of course, with a preponderance and emphasis on the artistic type of thinking. V.G. Belinsky owns the classic formula “Art is thinking in images.” The basic methodological principles in considering the problem of musical thinking are the ideas about the intonational nature of musical thought processes (B.V. Asafiev), about the unity of the sensory and intellectual sides of intonation as the main core of musical thinking (B.L. Yavorsky). In addition, in works in the field of modern musicology, musical thinking is considered as a unity of constructive-logical and sensory-emotional, as a process of artistic and intonational understanding of reality (M.G. Aranovsky, L.A. Mazel, V.V. Medushevsky, E. V. Nazaykinsky, M. I. Rotershtein, A. N. Sokhor, G. M. Tsypin, etc.).

Research results of B.L. Yavorsky reveals two aspects in intonation unity. This is the sensual side of intonation, manifested primarily in pitch, stability-instability, dynamic and timbre coloring. These are thought processes, according to the views of B.L. Yavorsky, expressed in the temporary development of intonation, in constructive terms, in the development of internal contradiction. Here it is most obvious that musical thinking belongs not only to the artistic, but also to the scientific and logical type. It is obvious, however, that the sensual and intellectual principles are not opposed here, but are distinguished as sides of a single thing - intonation.

The thesis “music is the art of intoned meaning” belongs to B.V. Asafiev, became one of classical formulas in the study of the problem of thinking in musical creativity. Actually, the concept of intonation in a broad sense was introduced into musicology by B.V. Asafiev. Here are some brief, formula-like Asafiev’s definitions of intonation: “intonation is the expression of human consciousness in sound”, “expression of imaginative thinking”, “sound-like identification of meaning”, “emotional-semantic tone of sound”, “intonation, that is, sound reproduction of the thinkable” .

V. Bobrovsky noted that in music that arises in the artistic consciousness, the image of reality is realized through a system of intonation conjugations. Here the emotional and rational series merge into an integral phenomenon - a musical intonation system, the basis of which is emotion - thought.

The most important functions of musical thinking are: analysis (selection, reasoning, consideration, comparison, comparison, analysis, auditory determination, emotional reaction, etc.) and synthesis (opinion, presentation, inference, conclusion, generalization, meaningful feelings and emotions, etc. ).

The most common ways of analyzing musical works and musical artistic movements have developed into certain types of analysis, although absolutely everything can be analyzed - from the artistic idea of a work to a specific means of expression, for example, strokes. As an example, let's highlight:

intonation analysis;

analysis of musical form;

analysis of musical style and genre;

analysis of means of musical expression: harmonic analysis, analysis of pitch, modal relationships, timbre palette, dynamic development, rhythmic basis, etc.;

performance analysis;

analysis of the relationship with other types of arts (literature, painting, choreography, etc.);

holistic analysis of a piece of music, etc.

The systematic implementation by students of artistic and intellectual operations is necessary condition development of musical and general thinking. Mastering in practice the work of various functions of musical thinking can be based on the experience in musicology and methodology that has already developed by that time. musical education. So, working on any music program at school, you can use to generalize the key concepts and topics proposed in D.B.’s system. Kabalevsky (the main genres and their features, what the music speaks about, musical speech, intonation, the construction of music, the music of my people, the musical image, etc.). These can also be algorithms for creative tasks according to Carl Orff (come up with a word or sentence, find a rhythm for it, come up with a melody for this word or sentence with the found rhythm, select several children's musical instruments and make accompaniment, etc.). Talking about conditions development of musical thinking, the following can be identified as the main ones:

Life experience, ideas about the world in images.

Musical experience, experience of musical impressions.

Development of musical ear, degree of development of elemental and complex abilities.

Quantity and quality of the studied repertoire (Tsypin G.M.).

Reliance on didactic principles in teaching (connection with life, scientific character, unity of the emotional and artistic, consistency, systematicity, clarity, accessibility, etc.)

Usage various methods and techniques that are optimal for solving problems in the process of musical education (not only problem-solving, gaming, etc.)

Systematic implementation of artistic and intellectual operations.

Therefore, everything in a child’s life is important: what phenomena he observed, what range of feelings and emotions he was able to experience or observe, what he empathized with and retained in his memory, what musicians he saw and heard, etc. And the teacher is required to understand the capabilities of the program that formed the basis of training for the qualitative development of musical thinking (of course, in conjunction with teaching methods).

Musical thinking can be characterized by the same epithets as thinking in general.

Qualities of thinking:

scale, activity, independence, intensity, depth, creative initiative, logic, maturity, flexibility, efficiency, originality, imagery, originality and others - are usually perceived with a plus sign and mean what a person should strive for in his development.

However, all these qualities can be contrasted with the opposite qualities of thinking:

limitedness, standardization, conservatism, dogmatism, illogicality, backwardness, underdevelopment, inhibition, passivity, superficiality, etc.

The combination of a number of qualities leads to the possibility of determining level of thinking. In the music pedagogical literature, a variety of typologies of levels of thinking are given, but for practical work the simplest model always remains relevant:

low levels of thinking.

The main criterion for the productivity of musical thinking is the knowledge of artistic meaning, content expressed in acoustic material forms.

Musical art stores emotional, spiritual information. One of its functions is to transmit this information from one person to another, from generation to generation. Information is imprinted in the system of meanings of the musical language. People can understand each other only by using the same system of meaning. It is impossible to study all the elements of musical language in lessons. Therefore, for the needs of music pedagogy, one should choose the most accessible elements, a kind of musical alphabet of meanings. Without exaggeration, we can say that all current methods of musical education offer a similar “alphabet” of a more or less standard type (orally analyze several key and particular elements of D.B. Kabalevsky’s system). It is necessary to organize the educational process so that the elements of musical language are deposited in the minds of children not as empty sound forms, but full of expressive meaning.

When solving any problem during musical activity, the teacher controls the process of musical thinking of students according to various external signs:

verbal activity (is not the main, but a by-product of musical activity);

creative performance (singing, playing instruments);

literary creativity; paintings;

musical movement, motor patterns, etc.

Koptseva Natalya Petrovna,

Doctor of Philosophy, Professor,

Dean of the Faculty of Art History and Cultural Studies,

head Department of Cultural Studies, Siberian Federal University, Krasnoyarsk [email protected]

Lozinskaya Vera Petrovna,

candidate of philosophical sciences,

Associate Professor, Department of Cultural Studies

Siberian Federal University, Krasnoyarsk [email protected]

The study of the functions of musical thinking should be preceded by a thorough study of its concept. Musical thinking is a special phenomenon, the study of which in Lately carried out mainly in the psychology of music. The selection of non-verbal (non-verbal) ways of thinking as a subject is due to a number of reasons.

First of all, it is the impossibility, with the help of the concept of verbal abstract-logical thinking, to reflect all the diversity of forms in the surrounding reality, to comprehend the Fullness of Being. The second reason is the need of modern philosophy to integrate the achievements of traditional rationalism with other ways of knowing the Universe. The third reason is the need, when analyzing mental processes of a dynamic nature, to use adequate methods of comprehension, to create not only rigid logical-conceptual models, but also more flexible plastic structures that could fully represent the deep essential foundations of reality in cultural and figurative terms. -artistic sphere.

Musical thinking is the highest form of auditory thinking. In turn, auditory thinking is a type of synthetic thinking, in which the synthesis of sensibility and rationality is presented in dialectical unity. Undoubtedly, any thought process is initially determined by visual-sensory mechanisms, called by psychologists the “first signaling system.” However, these processes are traditionally qualified as preceding mental activity itself. Thus, the “second signaling system” is necessarily based on the first, while the “first signaling system” has an autonomous existential status. In synthetic thinking, sensibility as such plays a more serious role, directly integrating into the rational structure, thereby not only transforming rational processes, but also itself undergoing a certain transformation under the influence of the rational component. Such sensibility, transformed and integrated into rational structures, as defined by V.I. Zhukovsky and D.V. Pivovarov, is called “secondary sensuality”.

Based on the concepts of “secondary sensibility”, “synthetic thinking”, “visual thinking”, a corresponding theory of the artistic image was developed, but based on the analysis of only fine art. Nevertheless, this theory of artistic image can serve as a methodological basis for the further development of the theory of synthetic thinking and the development of pedagogy of musical art.

Based on the theory of synthetic thinking, certain assumptions can be made related to auditory thinking and its highest form - musical thinking.

Auditory thinking is an indirect generalization, reflection, display of significant connections and relationships of objects of reality through a special sign representation.

It should be noted that the tendency in philosophical literature continues to be to reduce the process of indirect and generalized reflection by the subject of significant connections and relationships only to verbalized thinking. The tradition of relating thinking only to the verbal form is long-standing, and it is difficult to abandon it. However, at present, psychologists, studying complex mental activity that is based on specific spatial, force, etc. representations and proceeds in the form of action with external objects (schemes, design models, various kinds of dynamic subject situations), necessarily recognize that there are various shapes highly developed thinking, often closely intertwined and transforming into each other.

The problem of the reality of non-verbal thinking relatively recently became the subject of close attention of domestic philosophers. It is necessary to note the work of D.I. Dubrovsky. Summarizing psychophysiological observations, he comes to the conclusion about the reality of non-verbalized layers of “living thought”. At the same time, under the “living thought” of D.I. Dubrovsky means a thought that is actually experienced by a specific person at a given time interval (as opposed to a thought recorded in the text). For him, “living thought” is nothing more than thinking. “Even a living thought contained in a word still continues, pulsates, branches out in order to again find verbal forms and, leaving most of itself in them, move on.” According to D.I. For Dubrovsky, a synchronous cut of the field of consciousness of a moving thought opens two levels of current subjective reality: not yet verbalized and already verbalized. These levels form a dynamic structure, the dynamism of which lies in the following: the non-verbalized becomes verbalized, opening up more and more new layers of the non-verbalized, “facilitating their rise to the level of need and the possibility of adequate verbalization.” This means that non-verbal thought exists and is an indispensable component of cognitive processes. According to D.I. Dubrovsky, a weakly reflected structure of subjective reality emerges, the consideration of which when analyzing active consciousness becomes mandatory.

Among the definitions of the discussed layer of weakly verbalized subjective reality proposed in the psychological literature, the following seems adequate: auditory thinking is human activity, the product of which is the generation of new images, the creation of new sound forms that carry a certain semantic load and make the meaning audible. These images are distinguished by autonomy and freedom in relation to the object of perception.

Auditory thinking performs specific cognitive functions, dialectically complementing the conceptual study of an object. At the same time, it is capable of effectively reflecting almost any categorical relations of reality, but not through the designation of these relations by words, but through their embodiment in the spatio-temporal structure, transformations and dynamics of sensory images.

Auditory thinking has a synthetic character: it arises on the basis of verbal thinking, but due to the connection with transformed sensory material, it largely loses its verbalized character. At the same time, non-verbalized knowledge in images of auditory thinking can be verbalized under certain conditions.

Auditory thinking is a type of rational reflection of essential connections and relationships of things, carried out not on the basis of words of natural language, but directly on the basis of dynamically structured sound patterns. It has relative independence from material objects, existing practice and established sensory experience and connects abstract thinking with practice.

As a first approximation, the following levels of auditory thinking can be distinguished: 1) auditory thinking of the child; 2) auditory thinking of an adult listener; 3) auditory thinking of the performer; 4) auditory thinking of the composer. At first glance, this classification mixes the age approach (child - adult) and the specialized approach (professionals - non-professionals). In addition, the listener can be both a professional and a non-professional, a child or an adult. But in this case, it was important to emphasize certain specifics of each identified level of auditory thinking.

Currently, there are studies that indicate the primacy of non-verbal stages of mastering the surrounding world, as well as the possibility of non-verbal communication. Using sound as an expressive signal, young children are able to communicate with each other. As the child masters verbal thinking, the ability for purely auditory communication gradually decreases; at the same time, this circumstance allows us to speak about the universal nature of auditory communication as the embryo of musical thinking.

The listener's auditory thinking develops in a certain social environment, based on the sound space that surrounds him every day. That is why there are so many differences in assessments of this or that music. Full-fledged auditory thinking in the form of musical thinking develops when the child himself becomes familiar with the art of music. The ability for the highest form of auditory thinking - musical thinking - is largely determined genetically, as well as during prenatal development. This is evidenced by the biographies of many great composers. Common teaching of music in the 17th–19th centuries. contributed to the rise in the development of musical art in this era. However, musical thinking can be developed by being a music lover. The greater a person’s listening experience, the more new shades he is able to find in the work he performs, he is able to establish the style, era, method of composition, and find out what artistic movements contributed to the development of the composer. Moreover, he will receive this information while listening to a musical work of art.

The performer's auditory thinking also takes on the highest form of musical thinking and has its own specifics. This is an advanced level of perception of musical compositions. Many details that are inaccessible to an ordinary listener immediately become clear to the performer. The performer is focused on a certain quality of performance: he knows how to gain experience from the performance of musical works by other performers. Only the performer is able to fully appreciate all the technical difficulties in scoring a musical work. While working on the technique of performing a musical work, he discovers the abyss of semantic content of the musical work. A piece of music passed through the performer leaves immeasurably more in his soul than simply listened to. This does not mean that performance automatically contributes to insight into the deeper essence of musical existence. Nevertheless, there is an authoritative opinion that the education of a performer of a musical work is the education of a thinker.

The composer's auditory thinking is the highest level of not only auditory thinking in general, but also musical thinking. In reality, the composer’s musical thinking is condensed to such an extent that it can translate temporal characteristics into spatial ones. Thus, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart is known to say that he is able to see his future work with his spiritual gaze not in time sequence, as it will subsequently be performed, but at once, holistically, like a beautiful statue. Obviously, musical thinking of this level is capable of making a genuine breakthrough into the Infinite, the Whole, where different opposites come together.

Musical thinking is the highest form of auditory thinking, which assumes the presence of a work of musical art as a source of sound sensuality and rational discovery of the artistic idea of a musical work of art. The musical thinking of the composer creates a musical work of art as a source of sensuality and rationality, while the musical thinking of the performer and listener unfolds in the presence of a musical work created by the composer and existing in the form of a musical text.

The living existence of musical thinking acts as the realization of its own functions. In relation to musical thinking, the function is its activity in the living existence of culture, and musical thinking itself acts as a function of creating and transmitting cultural values in relation to the art of music. The functions of musical thinking are understood as its accomplishment, performance within a culture. This interpretation of functions is related to the etymology of this word: translated from Latin, function means accomplishing, executing. In the research literature, functions are most often interpreted as 1) type of activity; 2) a type of connection in which a change in one of the sides leads to a change in the second side, the second side is called a function of the first.

It must be emphasized that the functions of musical thinking differ from the functions of musical art, since musical thinking is a direct process, the fixation of which is possible only in the abstract language of philosophy, psychology and other humanities, while musical art is a system of works of musical art that have specific forms .

Musical thinking is a mediating link in resolving the dialectical contradiction between the sensual and rational aspects of thinking; it is a type of rational reflection of the essential connections and relationships of things. At the same time, musical thinking performs this reflection in a special sensual sound form, condensed in a work of musical art. It allows these essential connections to resonate musically.

The following functions of musical thinking can be distinguished: 1) epistemological; 2) ontological; 3) methodological; 4) communicative; 5) axiological; 6) ideological. Of course, the classification of these functions is not exhaustive. The types of functions generally accepted in philosophical logic are considered, which allows us to sufficiently fully reveal the specifics of musical thinking.

The epistemological function of musical thinking is as follows.

1. In the awareness of new ways of organizing spatial-temporal relations in the form of a musical artistic image. This design is a way of understanding real things and phenomena. An artistic image, being virtual, nevertheless models a real image of the world. Moreover, in the process of musical thinking, the cognition of such structural patterns is carried out that cannot be adequately expressed or presented otherwise than in the process of musical thinking. We are talking about the problem of expressing the ideal through the real, the infinite through the finite.

2. Musical thinking is the most adequate way of understanding the illogical, irrational foundations of culture in the broad sense of the word. Musical thinking reveals such patterns of reality that, in principle, cannot be given otherwise than in the form of musical thinking and, thus, leads the listener to the hidden, unmanifest essence of things, events, processes, makes this essence audible, reveals it.

3. Musical thinking builds a connection between the fluid procedural variability of human existence and abstract concepts and laws that describe this existence. Musical thinking forms such an understanding of the world, which is not just a “logical skeleton”, but allows us to understand the world in movement, formation, variability, processivity. A musical artistic image as a result of musical thinking is essentially a process.

4. Musical thinking restores the natural interdependence of things and phenomena in their fused interpenetration and confrontation, including in connections of a syncretic type, but models this interdependence in a logical, structurally formalized musical form. The sensual and rational in musical form, which is the materialization of musical thinking, are in dialectical unity. Unlike, perhaps, scientific knowledge, where the sensory platform is only the initial basis in the creation of a theoretical system, in artistic synthetic thinking the sensory accompanies the creative process from beginning to end, transforming into secondary sensibility, representing the sounding image of a previously intelligible essence.

5. Musical thinking reveals the inner essence of social processes. If it is impossible to express this by verbal means, musical thinking also takes on an ideological role. It is no coincidence that many informal associations are associated with one or another musical direction as a means of adequately expressing a certain worldview. Moreover, this is a manifestation of not just any mental states, and the expressions represented by alternative musical styles also represent the philosophy of life of the most modern generation.

The epistemological function of musical thinking in relation to cultural values is manifested in several aspects.

1. In a situation of life choice, the epistemological mechanisms of musical thinking are capable of initiating the process of life choice, inducing it, “sharpening” those mental forms that will demonstrate the need for this choice. This or that musical work is capable of manifesting opposing forms of life, giving them a sounding form, and demonstrating the situation of life choice through musical means.

2. Epistemological aspects of musical thinking “work” when it is through the relationship with a piece of music that the individual realizes the fact that life choice in general and value orientation in particular is not a one-time act, but a long-term state of life. Different works of musical art embody different artistic ideas, each of which seems extremely valuable to the individual. Musical thinking itself creates an understanding of the plurality of cultural values embodied in various musical works.

3. Epistemological mechanisms of musical thinking help to identify the inconsistency of different artistic ideas embodied in various musical works. Thus, the value of human life may be the opposite of the value of giving one’s life for another person. Each of the values is embodied in works of musical art that equally have high cultural significance. By entering into an artistic relationship with different musical works, an individual “cultivates” in himself an understanding of the equal significance of values that are opposite in content, each of which can be in demand at different periods of his life.

4. The epistemological function of musical thinking always lies at the basis of the design reality created in the process of direct relation to generally significant cultural samples embodied in a musical work. A piece of music embodies values that should be cultivated, created and transmitted. It is the epistemological function of musical thinking that leads to the understanding of this need.

The ontological function of musical thinking is to create a sound image, a sound picture of the world. The ontological function of musical thinking is associated with at least two factors.

1. Musical thinking as a reflection of the universal harmony of the Universe, refracted in specifically human means of recreating this harmony. Musical thinking is understood here as the most adequate human desire for the Absolute, given in a dynamic aspect.

2. Musical thinking is the expression of human content in a sensually given musical and artistic form.

The image of the world that is formed in the process of musical thinking necessarily has the status of a cultural value, since it is in it that the very design reality that constitutes the content of the value is embodied. The form of a musical work, acting as a representative of the Absolute, Infinite, Whole, is an ideal, the highest cultural value for a person. Achieving the state of infinity is the ultimate goal for the design of reality. A musical work, acting as a representative of the Absolute, offers the individual a cultural form of value goal setting.

The musical picture of the world is distinguished by the unity of subject-object relations in the aspect of secondary sensuality. Secondary sensuality is a “subdued” picture of the world in the human subject. The external world exists inside the subject in the form of sensations, perceptions, and ideas. In addition, in secondary sensibility, not only the external world is represented, as the “world of phenomena,” but also the internal, deep essence outside the phenomenon of secondary sensibility, which is not objectively manifested. A work of art is always a manifestation, a cognition of this hidden meaning and meaning. This is its value. Otherwise, the very vital necessity of a work of art disappears.

Musical thinking does not always have a holistic form. However, it creates a picture of the world that itself contains the potential for its own development. It is this quality of the musical picture of the world that makes it a real cultural value. Music is a process of transition from non-existence to existence and back. It demonstrates not the things themselves, but the process of their birth, formation, death, reproduction, etc. Thus, music is a border, a bridge that actualizes the very process of generating both speculative and physical world. The miracle of the emergence of “something” from “nothing” is represented, expressed, actualized in musical thinking.

The value aspect of the ontological function of musical thinking is that musical picture world creates the basis for designing reality, offers the highest examples, standards for humans, expressed in a harmonious, sounding, universal form.

The musical picture of the world is always in tune with its era, expresses its spirit and at the same time anticipates future social changes.

The methodological function of musical thinking is closely related to the ontological and epistemological functions. The methodological function forms the process of cognition of objective reality through musical thinking. The musician enters the space ideal relationship himself as a finite being with an infinite Absolute, the representative of which is a work of musical art. It is important to emphasize that the methodological function can only be carried out by the master himself, and in no way can this function be imposed on him from the outside. Methodology is a system of principles and ways of organizing the creative process; it allows you to most effectively implement creative tasks.

10

Musical thinking acts as the creator of cultural value in the aspect of methodology in a situation of life choice. This choice can be made for various reasons. The methodological function of musical thinking predetermines both the choice itself and its result. A musical work of art “demands” from the individual creative approach to life choice, forces us to design reality by mobilizing all the creative abilities of a person.

The methodological function is capable of anticipating the final result, and in this sense it comes into contact with the prognostic and heuristic functions. But a specifically methodological function is the gradual planning of the creative process itself. The methodology of musical thinking is based on all previous experience in constructing musical material. If there is a denial of existing values, then musical thinking is obliged to provide new principles for organizing an artistic form that embodies one or another cultural value. Avant-garde examples of musical art are no exception. They must prove their cultural value and reveal the method of their reconstruction.

The communicative function of musical thinking involves:

1) the presence of certain information that must be conveyed to the recipient;

2) the presence of a certain semantic system, a language within which communication is carried out;

3) the presence of a perceiver capable of “deciphering” the sign structure into universal human meanings originally inherent in a musical work.

The communicative function of musical thinking appears in several forms.

1. It is closely related to the meaning-generating function of musical thinking. The birth of a new meaning, first of all, involves going beyond the subjective-human to the level of the universal. This access to the level of universal and absolute knowledge in culture received the meaning of “Revelation”. The new arises in the space of relationship, the “meeting place” of the composer, performer, listener and the Absolute.

This aspect of the communicative function of musical thinking is most adequate to the situation of creating and transmitting cultural values. There is no doubt that cultural values are created through the implementation of all functions of musical thinking without exception, but it is the communicative function that makes it possible to connect subjective reality with objective reality, which is the condition and form of a value relationship in general, as well as its goal as a good. The highest good - the connection of the finite and the infinite - as the highest value is realized through the communicative function of musical thinking.

2. Communication is impossible without a certain system, therefore, musical thinking has its own language that adequately reflects musical meanings. The problem of the sign aspect of musical thinking is currently far from its final resolution, which does not give reason to reject the very possibility of objective “decipherment” musical meanings by verbal means.

3. The problem of adequate perception music information requires significant effort on the part of the recipient. In other words, the process of perception presupposes the same stages of development musical content, previously undertaken by the composer and performer, i.e. the process of perception involves intense work of musical thinking. The perception of music (primarily this applies to classical works of art) must be taught purposefully and methodically. What is required is “initiation”, familiarization with the cultural value of a work of art.

This entire study is devoted to the axiological function of musical thinking. It should be noted, however, that the value of musical thinking is revealed through the implementation of all the functions discussed above. Through its functioning, the musical thinking of the composer creates cultural values, the musical thinking of the performer and listener preserves them and transmits them from individual to individual, from this historical era to another.

As G.G. points out. Kolomiets, one should distinguish between the value of music and the value in music. The value of music itself is its purpose in culture. Values in music are the value-semantic meanings that the subject imparts to music and its forms. The present study takes into account both aspects, but emphasizes how the art of music creates and distributes value within a culture.

L.A. writes about value dominants in the work of composers as the basis of their worldview. Zaks. He solves the problem of mastering music in a culture where the central place is occupied by values created by man, and notes the following: “If the content core of spiritual culture is the basic values of the human spirit (aesthetic, moral, worldview), then music is an intonational way of existence of these values, moreover, in this or that intense subjective integrity and active orientation towards reality, which is a living human relationship with the world.”

L.A. Sachs identified five spiritual and cultural contexts of musical art: subject-matter, spiritual-value (value-semantic), cultural-psychological, semiotic, and the context of sociocultural forms of communication (methods of social functioning).

The basis of the value hierarchy is the principle of opposites. Each value has a corresponding “anti-value”: truth – error; good evil; beautiful - ugly; sublime - base. The value-semantic plan also includes the value content of individual “fragments” of the world, nature, human life and the humanistic problems emanating from them about the meaning of life, the purpose of man, the desire for beauty, goodness, happiness, determined by needs. The source of value orientations, according to the scientist’s conviction, are monuments and texts of the era: works of art, works of philosophers, aestheticians, culturologists, art historians. Since values are mastered by an individual through the experience of a certain cultural objectivity, then, being central, the spiritual-value context is systemically connected with the objective and cultural-psychological.

The artistic attitude to the world is formed on a historically specific basis. The spiritual and value structure of artistic consciousness determines the choice of life material, its ideological and emotional nature of perception and, accordingly, its intonation and genre origins. These cultural layers are appreciated both by individual artists and by whole artistic directions. For example, images of the world, man, and freedom are filled with different meanings in the value systems of Mozart and Glinka, Gluck and Liszt, Wagner and Prokofiev. The sounding tragedy of the music of Bach, Schubert, Mussorgsky is different, since it is included in various systems of understanding the world and value interpretation.

From the point of view of modern philosophy of culture, L.A. Sachs identified three main types of values expressed in music: aesthetic, moral, ideological. The main types of values are not only interconnected, but also penetrate each other and form a synthesis in a musical work of art. At the same time, the type and state of culture reveal a value dominant of musical figurative meaning: moral and worldview in Bach, Mahler, Shostakovich; aesthetic and worldview in Berlioz, Liszt, Wagner; aesthetic in Chopin, Rachmaninov, Ravel. Isolating the value dominant of a composer’s work or movement is the most general character, but it's useful. The genre spectrum of creativity and genre-thematic preferences are determined by the value dominant of a particular culture. Appeal to the spiritual-value context is methodologically important not only because it gives an idea of the spiritual environment of the existence of music, but also because “otherwise it researchfully “turns” the music itself, deepens its comprehension, forcing us to realize, differentiate and then synthesize the key elements into a specific integrity. ideological and semantic moments of its spiritual content, which often remain in vain in the practice of musicological analysis, or are dissolved in a purely emotional interpretation.”

Thus, the axiological function of musical thinking is the creation of cultural forms, the relationship to which is directly experienced as a value that has the character of a project reality for a person. A musical work of art acts as a materialized value, it is a representative of the highest benefit, it is a criterion separating positive and negative (evaluation criterion); it is the embodiment of the higher, separated from the lower. Achieving the values embodied in a musical work of art becomes the basis for designing the future and comparing one’s design with the design of the future of other people.

Musical thinking in the aspect of its axiological function connects individual consciousness and mass consciousness, subjective reality with objective reality. The axiological function of musical thinking makes it a unique and indispensable mechanism for culture for the creation, preservation and dissemination of cultural values.

The worldview function of musical thinking is closely related to all of the above functions, especially the axiological one. Updated here antique performance about music as the ideal of the Universe, a form of the highest orderliness of human life. Confucius believed that musical thinking creates a model of a society of great unity, a symphony, where individual sounds, occupying a strictly defined place, form harmony. Harmony directly depends on the rigid definition of sound; it is impossible to swap sounds and maintain the original harmony.

However, the ideological function of musical thinking affects not only the objectification of music as a representative of a harmoniously arranged Absolute, it is associated with the ideal of human existence, where all structural elements of a person are ordered and dynamically harmonized: carnal, mental and spiritual; within the soul the conscious, unconscious and subconscious are harmonized; inside the conscious, the sensual and rational are harmonized, inside the unconscious - the instincts of life and death.

The worldview function of musical thinking reinforces confidence in the existence of the greatest cultural values, the limits of which are Truth, Goodness and Beauty. The reality of musical thinking gives the status of the reality of harmony and causes the need to harmonize one’s individual and social existence.

As V.I. writes Plotnikov, “historically, value can be conceptualized as such a universal form of design, which is modified in the conditions of civilization, opening up new horizons for it. In this historical dimension, it is certainly higher, richer and more promising than the equally universal form of design that preceded it, which was useful for primitiveness. But from a transcendental point of reference (and in modern times the future is becoming increasingly clear), none of them provides an optimal match for the stability of social existence, sufficient diversity of culture and the free development of the individual.” The scientist writes that orientation towards benefit (i.e. towards the near future) creates the utmost stability of the communal form of existence, but at the expense of minimal cultural diversity and an almost complete absence of personal identity. On the contrary, orientation towards value (i.e. the very ability to project the distant future) creates the utmost diversity of culture and sufficient freedom of personal self-determination, but at the expense of the maximum instability of social forms of existence and increasing sociocultural differences between individuals, which together gives rise to hatred and enmity , presence, mistrust as inevitable companions of the civilizational form of human life.

The ideological function of musical thinking creates an ideal project reality, where social forms of being correspond to the diversity of culture and the free development of the individual, and also allows us to accept existing existence as it is - in the contradictory nature of its tendencies, values, and ideals.

Analysis of the various functions of musical thinking allows us to propose another definition of musical thinking.

Musical thinking is a mental, meaning-generating, value-orienting activity, which is based on the intellectual operation of semantically defined blocks that arise in the space of the relationship between the composer and artistic musical material, on the one hand, and expressed in the iconic specificity of the musical text; on the other hand, arising in the process of interaction between the listener and performer and the musical work, the result of which is a musical artistic image. Musical thinking is capable of reflecting various spheres of objective reality, often inaccessible to verbal expression, creating and disseminating cultural values, acting as their materialized form.

Literature

1. Zhukovsky V.I., Pivovarov D.V. Visible essence (visual thinking in the fine arts). – Sverdlovsk: Ural University, 1991. – 284 p.

2. Koptseva N.P., Zhukovsky V.I. An artistic image as a result of a playful relationship between a work of fine art as an object and its viewer / Journal of the Siberian Federal University. Series “Humanities” – 2008 – T.1 – No. 2. P. 226–244.

3. Koptseva N.P., Zhukovsky V.I. The importance of the viewer in the process of the relationship between a person and a work of fine art / Territory of Science - 2007 - No. 1. P. 95–102.

4. Dubrovsky D.I. The problem of the ideal. M.: Mysl, 1983. 230 p.

5. Kolomiets, G.G. The value of music: philosophical aspect / G.G. Kolomiets. Ed. 2nd. M.: LKI Publishing House, 2007. 536 p.

6. Zaks L. Music in the context of spiritual culture // Criticism and musicology: Collection. articles. Vol. 3. L.: Muzyka, 1987. pp. 46–48.

7. Modern philosophical dictionary / under general. ed. Doctor of Philology prof. V.E. Kemerovo. 2nd ed., rev. and additional London; Frankfurt am Main; Paris; Luxembourg; Moscow; Minsk: PANPRINT, 1998. 1064 p.

Municipal budgetary educational institution

"Children's Art School"

Report

"Musical Thinking"

Compiled by:

piano teacher

MBOUDOD "DSHI"

Thinking- the highest level of human knowledge of reality.

Through the senses - these are the only channels of communication between the body and the outside world - information enters the brain. The content of information is processed by the brain. The most complex (logical) form of information processing is the activity of thinking. Solving the mental problems that life poses to a person, he reflects, draws conclusions and thereby learns the essence of things and phenomena, discovers the laws of their connection, and then transforms the world on this basis.

Thinking is not only closely connected with sensations and perceptions, but it is formed on their basis.

Transition from sensation to thought. Mental operations are varied. This is analysis and synthesis, comparison, abstraction, specification, generalization, classification. Which logical operations a person will use will depend on the task and on the nature of the information that he is subjected to mental processing. Mental activity is always aimed at obtaining some result. Among the creators of concepts related to musical thinking, he holds one of the first places. The essence of his teaching is as follows: musical thought manifests itself and expresses itself through intonation. Intonation like base element musical speech is the concentrate, the semantic fundamental principle of music. An emotional reaction to intonation, penetration into its expressive essence is the starting point of the processes of musical thinking.

Soviet sociologist A. Sokhor, identifying the basic patterns of musical thinking as a social phenomenon, rightly believes that in addition to “ ordinary concepts, expressed in words, and ordinary visual representations that materialize in visible expressions, the composer necessarily - and very widely - uses specifically musical “concepts”, “ideas”, “images”

Musical thinking is carried out on the basis of musical language. It is capable of structuring the elements of musical language, forming a structure: intonation, rhythmic, timbre, thematic, etc. One of the properties of musical thinking is musical logic. Musical thinking develops in the process of musical activity. Musical information is obtained and transmitted through musical language, which can be mastered by directly engaging in musical activity. A musical language is characterized by a certain “set” of stable types of sound combinations (intonations), subject to the rules (norms) of their use. It generates the texts of musical messages.

The structure of the text of the musical message is unique and inimitable. Each era creates its own system of musical thinking, and each musical culture generates its own musical language. Musical language forms musical consciousness exclusively in the process of communicating with music in a given social environment.