Unreal figures in the real world. Impossible figures. stage. Project implementation activities

GU Osmeryzhskaya main comprehensive school

Direction: physics and mathematics

Performer of the work : Dippel Sergey, 6th grade student of the Osmeryzhsk secondary school, Pavlodar region, Kachira district, Osmeryzhsk village

Head of work: Dovzhenko Natalya Vladimirovna mathematics teacher at Osmeryzhskaya secondary school

year 2013

Resume/abstract/………………………………………………………………2

Introduction……………………………………………………………………………….........3

1. A little bit of history……………………………………………..………….5

2. Types of impossible figures…………….…………………………………….9

3. Oscar Ruthersward – father of the impossible figure……….………………..16

4. Impossible figures are possible!……………………………………...18 5. Application of impossible figures……………………………………..……19

Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………….....21

References……………………………………………………………22

Resume /abstract/

Project stages:

Stage 1.

Statement of the problem, setting goals, objectives of information and research work;

Conducting conversations about impossible figures;

Staging problematic issue, motivation to implement the project;

Carrying out preliminary work on the topic “Impossible figures”;

Discussion and compilation step-by-step plan work, creating a bank of ideas and proposals. Selection of information sources.

Stage 2. Project implementation activities.

Information and educational conversations;

Information retrieval work;

Experimental work;

Literature review

Achievements of goals

Introduction

For some time now I have been interested in figures that at first glance seem ordinary, but upon closer inspection you can see that something is wrong with them. The main interest for me was the so-called impossible figures, looking at which one gets the impression that to exist in real world They can not. I wanted to know more about them.

Despite the fact that impossible figures have been known almost since the time rock art, their systematic study began only in the middle of the 20th century, that is, almost before our eyes, and before that mathematicians dismissed them as an annoying misunderstanding.

In 1934, Oscar Reutersvard accidentally created his first impossible figure, a triangle made of nine cubes, but instead of correcting anything, he began creating other impossible figures one after another.

Even such simple volumetric shapes as a cube, pyramid, parallelepiped can be represented as a combination of several figures located at different distances from the observer’s eye. There should always be a line along which the images of individual parts are combined into a complete picture.

“An impossible figure is a three-dimensional object made on paper that cannot exist in reality, but which, however, can be seen as a two-dimensional image.” This is one of the types optical illusions, a figure that at first glance seems to be a projection of an ordinary three-dimensional object, upon careful examination of which contradictory connections of the elements of the figure become visible. An illusion is created of the impossibility of the existence of such a figure in three-dimensional space.

Despite a significant number of publications about impossible figures, their clear definition has not been formulated in essence. You can read that impossible figures include all optical illusions associated with the peculiarities of our perception of the world. On the other hand, a person can show you a figure of a green man or with ten arms and five heads and say that all these are impossible figures. At the same time, he will be right in his own way. After all, there are no green people with ten legs. Therefore, by impossible figures we will understand flat images of figures perceived by a person unambiguously, as they are drawn without human perception of any additional, actually not drawn images or distortions and which cannot be represented in three-dimensional form. The impossibility of representation in three-dimensional form is understood, of course, only directly, without taking into account the possibility of using special means in the manufacture of impossible figures, since an impossible figure can always be made by using an ingenious system of slots, additional supporting elements and bending the elements of the figure, and then photographing it under the right angle

I was faced with the question: “Do impossible figures exist in the real world?”

Project goals:

1. Find out how unreal figures are created.

2. Find areas of application of impossible figures.

Project objectives:

1. Study literature on the topic “Impossible figures.”

2. Make a classification of impossible figures.

3. Consider ways to construct impossible figures.

4.Create an impossible figure.

The topic of my work is relevant because understanding paradoxes is one of the signs of the type of creative potential that the best mathematicians, scientists and artists possess. Many works with unreal objects can be classified as “intellectual” math games" Such a world can only be modeled using mathematical formulas; humans simply cannot imagine it. And impossible figures are useful for the development of spatial imagination. A person tirelessly mentally creates around himself something that will be simple and understandable for him. He cannot even imagine that some objects around him may be “impossible.” In fact, the world is one, but it can be viewed from different angles.

Impossible figures

A little bit of history

Impossible figures are quite often found in ancient engravings, paintings and icons - in some cases we have obvious errors in the transfer of perspective, in others - with deliberate distortions caused by artistic design.

We are used to believing photographs (and a few in to a lesser extent- drawings and drawings), naively believing that they always correspond to some kind of reality (real or fictional). An example of the first is a parallelepiped, the second is an elf or other fairy-tale animal. The absence of elves in the region of space/time we observe does not mean that they cannot exist. They still can (which is easy to verify with the help of plaster, plasticine or papier-mâché). But how to draw something that cannot exist at all?! What can’t be designed at all?!

There is a huge class of so-called “impossible figures”, mistakenly or deliberately drawn with errors in perspective, resulting in funny visual effects that help psychologists understand the principles of the (sub)conscious.

In medieval Japanese and Persian painting, impossible objects are an integral part of the oriental artistic style, which gives only a general outline of the picture, the details of which the viewer “has” to think out independently, in accordance with his preferences. Here is the school in front of us. Our attention is drawn architectural structure in the background, the geometric inconsistency of which is obvious. It can be interpreted as either the inner wall of a room or the outer wall of a building, but both of these interpretations are incorrect, since we are dealing with a plane that is both an outer and an outer wall, that is, the picture depicts a typical impossible object.

Paintings with distorted perspective can be found already at the beginning of the first millennium. In a miniature from the book of Henry II, created before 1025 and kept in the Bavarian state library in Munich, Madonna and Child is painted. The painting depicts a vault consisting of three columns, and the middle column, according to the laws of perspective, should be located in front of the Madonna, but is located behind her, which gives the painting the effect of unreality.

In the article "Bringing order to the impossible" ( impossible.info/russian/articles/kulpa/putting-order.html) the following definition of impossible figures is given: " An impossible figure is a flat drawing that gives the impression of a three-dimensional object in such a way that the object suggested by our spatial perception cannot exist, so that the attempt to create it leads to (geometric) contradictions clearly visible to the observer". The Penroses write approximately the same thing in their memorable article: " Each separate part the figure looks like a normal three-dimensional object, but due to the incorrect connection of the parts of the figure, the perception of the figure completely leads to the illusory effect of impossibility", but none of them answers the question: why is all this happening?

Meanwhile, everything is simple. Our perception is designed in such a way that when processing a two-dimensional figure that has signs of perspective (i.e. volumetric space), the brain perceives it as three-dimensional, choosing the simplest method of converting 2D to 3D, guided by life experience, and as was shown above, real prototypes“impossible” figures are rather sophisticated designs with which our subconscious is unfamiliar, but even after becoming familiar with them, the brain still continues to choose the simplest (from its point of view) transformation option, and only after lengthy training does the subconscious finally “enter the situation” and the apparent abnormality of the “impossible figures” disappears.

Let's start with the easy one. Consider a painting (yes, yes, a painting, not a computer-generated photorealistic drawing) drawn by Flemish artist named Jos de Mey/Jos de Mey. The question is - what physical reality could it correspond to?

At first glance, the architectural structure seems impossible, but after a moment’s hesitation, the consciousness finds a saving option: the brickwork is in a plane perpendicular to the observer and rests on three columns, the tops of which seem to be located at an equal distance from the masonry, but in fact the empty space is simply “hidden” “due to the “successfully” chosen projection. After consciousness has “deciphered” the picture, it (and all similar images) is perceived completely normally and geometric contradictions disappear as imperceptibly as they appeared.

Impossible painting by Jos de May

Consider the famous painting by Maurits Escher “Waterfall” and its simplified computer model, made in a photorealistic style. At first glance, there are no paradoxes; before us is an ordinary picture depicting... a drawing of a perpetual motion machine!!! But, as you know from a school physics course, a perpetual motion machine is impossible! How did Escher manage to depict in such detail something that could not exist in nature at all?!

Perpetual motion machine in the engraving "Waterfall" by Escher.

Computer model of Escher's perpetual motion machine.

When trying to build an engine according to a drawing (or upon careful analysis of the latter), the “deception” immediately emerges - in three-dimensional space such designs are geometrically contradictory and can only exist on paper, that is, on a plane, and the illusion of “volume” is created only due to signs of perspective ( in this case - deliberately distorted) and in a drawing lesson we will easily get two points for such a masterpiece, pointing out errors in the projection.

Types of impossible figures.

"Impossible figures" are divided into 4 groups. So, the first one:

An amazing triangle - tribar.

This figure is perhaps the first impossible object published in print. It appeared in 1958. Its authors, father and son Lionell and Roger Penrose, a geneticist and mathematician respectively, defined the object as a "three-dimensional rectangular structure." It was also called "tribar". At first glance, the tribar appears to be simply an image of an equilateral triangle. But the sides converging at the top of the picture appear perpendicular. At the same time, the left and right edges below also appear perpendicular. If you look at each detail separately, it seems real, but, in general, this figure cannot exist. It is not deformed, but the correct elements were incorrectly connected when drawing.

Here are some more examples of impossible figures based on the tribar.

|

Triple Warped Tribar 12 Cube Triangle | |

|

Winged Tribar Triple Domino The introduction to impossible figures (especially those performed by Escher) is, of course, stunning, but the fact that any of the impossible figures can be constructed in the real three-dimensional world is perplexing. As you know, any two-dimensional image is a projection of a three-dimensional figure onto a plane (sheet of paper). There are quite a lot of projection methods, but within each of them the mapping is carried out uniquely, that is, there is a strict correspondence between a three-dimensional figure and its two-dimensional image. However, axonometric, isometric and other popular methods of projection are unidirectional transformations carried out with loss of information, and therefore the inverse transformation can be performed in an infinite number of ways, that is, a two-dimensional image corresponds to an infinite number of three-dimensional figures and any mathematician can easily prove that such a transformation is possible for any two-dimensional image. That is, in fact, there are no impossible figures! Let's return to the Penrose Triangle and try to construct a three-dimensional figure, the projection of which onto a two-dimensional plane would look like the indicated image. Naturally, it will not be possible to solve such a problem directly, but if you think carefully and choose correct angle, then... one of the possible options is shown in the figure.

Possible impossible Penrose Triangle. Here's another display from Mathieu Hemakerz. Possible options there is a lot of reverse mapping. So many. Infinitely many!

The same Penrose Triangle from different angles. By the way, the Penrose Triangle is immortalized in the form of a statue in Perth (Australia). Created by artist Brian McKay and architect Ahmad Abas, it was erected in Claisebrook Park in 1999 and now everyone passing by can see the next "impossible" figure.

Perose Triangle in Australia But as soon as you change the angle of view, the triangle turns from “impossible” into a real and aesthetically unattractive structure that has nothing to do with triangles.

This is what the Penrose Triangle actually looks like. |

Endless staircase

This figure is most often called the “Endless Staircase”, “Eternal Staircase” or “Penrose Staircase” - after its creator. It is also called the "continuously ascending and descending path."

This figure was first published in 1958. A staircase appears before us, seemingly leading up or down, but at the same time, the person walking along it does not rise or fall. Having completed his visual route, he will find himself at the beginning of the path.

The “Endless Staircase” was successfully used by the artist Maurits K. Escher, this time in his lithograph “Ascent and Descend”, created in 1960.

Staircase with four or seven steps. The creation of this figure with a large number of steps could have been inspired by a pile of ordinary railroad sleepers. When you are about to climb this ladder, you will be faced with a choice: whether to climb four or seven steps.

The creators of this staircase took advantage of parallel lines to design the end pieces of the equally spaced blocks; Some blocks appear to be twisted to fit the illusion.

Space fork.

The next group of figures is collectively called the “Space Fork”. With this figure we enter into the very core and essence of the impossible. Perhaps this is the most numerous class impossible objects.

This notorious impossible object with three (or two?) teeth became popular with engineers and puzzle enthusiasts in 1964. The first publication dedicated to the unusual figure appeared in December 1964. The author called it a “Brace consisting of three elements.”

WITH practical point From our point of view, this strange trident or clamp-like mechanism is absolutely inapplicable. Some simply call it an "unfortunate mistake." One of the representatives of the aerospace industry proposed using its properties in the construction of an interdimensional space tuning fork.

Impossible boxes

Another impossible object appeared in 1966 in Chicago as a result of original experiments by photographer Dr. Charles F. Cochran. Many lovers of impossible figures have experimented with the Crazy Box. The author originally called it the "Free Box" and stated that it was "designed to send impossible objects to large quantities".

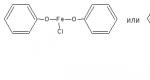

The “crazy box” is the frame of a cube turned inside out. The immediate predecessor of the Crazy Box was the Impossible Box (by Escher), and its predecessor in turn was the Necker Cube.

It is not an impossible object, but it is a figure in which the depth parameter can be perceived ambiguously.

When we look at the Necker cube, we notice that the face with the dot is either in the foreground or in the background, it jumps from one position to another.

Oscar Ruthersward - father of the impossible figure.

The “father” of impossible figures is the Swedish artist Oscar Rutersvard. Swedish artist Oscar Ruthersvard, a specialist in creating images of impossible figures, claimed that he was poorly versed in mathematics, but, nevertheless, elevated his art to the rank of science, creating a whole theory of creating impossible figures according to a certain number of patterns.

A pair of impossible figures by Oscar Reutersvärd.

He divided the figures into two main groups. He called one of them “true impossible figures.” These are two-dimensional images of three-dimensional bodies that can be colored and shadowed on paper, but they do not have a monolithic and stable depth.

Another type is dubious impossible figures. These figures do not represent single solid bodies. They are a combination of two or more figures. They cannot be painted, nor can light and shadow be applied to them.

A true impossible figure consists of a fixed number of possible elements, while a doubtful one “loses” a certain number of elements if you follow them with your eyes.

One version of these impossible figures is very easy to do, and many of those who mechanically draw geometric figures when talking on the phone have done this more than once. You need to draw five, six or seven parallel lines, finish these lines at different ends in different ways - and the impossible figure is ready. If, for example, you draw five parallel lines, then they can end up as two beams on one side and three on the other.

In the figure we see three options for dubious impossible figures. On the left is a three-seven beam structure, built from seven lines, in which three beams turn into seven. The figure in the middle, built from three lines, in which one beam turns into two round beams. The figure on the right, constructed from four lines, in which two round beams turn into two beams

During his life, Ruthersvard painted about 2,500 figures. Ruthersvard's books have been published in many languages, including Russian.

Impossible figures are possible!

Many people believe that impossible figures are truly impossible and cannot be created in the real world. But we must remember that any drawing on a sheet of paper is a projection of a three-dimensional figure. Therefore, any figure drawn on a piece of paper must exist in three-dimensional space. Impossible objects in paintings are projections of three-dimensional objects, which means that objects can be realized in the form sculptural compositions. There are many ways to create them. One of them is the use of curved lines as the sides of an impossible triangle. The created sculpture looks impossible only from a single point. From this point, the curved sides look straight, and the goal will be achieved - a real "impossible" object will be created.

Russian artist Anatoly Konenko, our contemporary, divided impossible figures into 2 classes: some can be simulated in reality, while others cannot. Models of impossible figures are called Ames models.

I made my own impossible figure. I took forty-two cubes and glued them together to form a cube with part of the edge missing. I note that to create a complete illusion, the correct angle of view and the correct lighting are necessary.

I create my impossible figures using O. Ruthersward's advice. I drew seven parallel lines on paper. I connected them from below with a broken line, and from above I gave them the shape of parallelepipeds. Look at it first from above then from below. You can come up with an infinite number of such figures.

Application of impossible figures

Impossible figures sometimes find unexpected uses. Oscar Ruthersvard talks in his book "Omojliga figurer" about the use of imp art drawings for psychotherapy. He writes that the paintings, with their paradoxes, evoke surprise, focus attention and the desire to decipher. Psychologist Roger Shepard used the idea of a trident for his painting of the impossible elephant.

In Sweden, they are used in dental practice: by looking at pictures in the waiting room, patients are distracted from unpleasant thoughts in front of the dentist’s office.

Impossible figures inspired artists to create a whole new movement in painting called impossibilism. Impossibilists include Dutch artist Escher. He is the author of the famous lithographs “Waterfall”, “Ascent and Descent” and “Belvedere”. The artist used the “endless staircase” effect discovered by Rootesward.

Abroad, on city streets, we can see architectural embodiments impossible figures.

Most known use impossible figures in popular culture- logo of the automobile concern "Renault"

Mathematicians claim that palaces in which you can go down the stairs leading up can exist. To do this, you just need to build such a structure not in three-dimensional, but, say, in four-dimensional space. And in virtual world, which modern computer technology reveals to us, and that’s not what you can do. This is how the ideas of a man who, at the dawn of the century, believed in the existence of impossible worlds are being realized today.

Conclusion.

Impossible figures force our minds to first see what should not be, then look for the answer - what was done wrong, what is the hidden essence of the paradox. And sometimes the answer is not so easy to find - it is hidden in the optical, psychological, logical perception of the drawings.

The development of science, the need to think in new ways, the search for beauty - all these requirements modern life They force us to look for new methods that can change spatial thinking and imagination.

After studying the literature on the topic, I was able to answer the question “Are there impossible figures in the real world?” I realized that the impossible is possible and unreal figures can be made with your own hands. I created the Ames model of the Impossible Cube. After looking at ways to construct impossible figures, I was able to draw my own impossible figures. I was able to show that

Conclusion: All impossible figures can exist in the real world.

There are many more areas where impossible figures will be used.

Thus, we can say that the world of impossible figures is extremely interesting and diverse. The study of impossible figures is quite important from a geometry point of view. The work can be used in mathematics classes to develop students' spatial thinking. For creative people Those who are prone to invention, impossible figures are a kind of lever for creating something new and unusual.

Bibliography

Levitin Karl Geometrical Rhapsody. - M.: Knowledge, 1984, -176 p.

Penrose L., Penrose R. Impossible objects, Quantum, No. 5, 1971, p. 26

Reutersvard O. Impossible figures. – M.: Stroyizdat, 1990, 206 p.

Tkacheva M.V. Rotating cubes. – M.: Bustard, 2002. – 168 p.

Internet resources:

http://wikipedia.tomsk.ru

http://www.konenko.net/imp.htm

http://www.im-possible.info/russian/articles/reut_imp/

Our eyes cannot know

the nature of objects.

So don’t force it on them

delusions of reason.

Titus Lucretius Carus

The common expression “optical illusion” is inherently incorrect. The eyes cannot deceive us, since they are only an intermediate link between the object and the human brain. Optical illusion usually occurs not because of what we see, but because we unconsciously reason and involuntarily get mistaken: “the mind can look at the world through the eye, and not through the eye.”

One of the most spectacular directions artistic movement optical art (op-art) is imp-art (impossible art), based on the image of impossible figures. Impossible objects are drawings on a plane (any plane is two-dimensional) depicting three-dimensional structures that are impossible to exist in the real three-dimensional world. Classic and one of the most simple figures is impossible triangle.

In an impossible triangle, each angle is itself possible, but a paradox arises when we consider it as a whole. The sides of the triangle are directed both towards and away from the viewer, so its individual parts cannot form a real three-dimensional object.

Strictly speaking, our brain interprets a drawing on a plane as a three-dimensional model. Consciousness sets the “depth” at which each point of the image is located. Our ideas about the real world face a contradiction, some inconsistency, and we have to make some assumptions:

- straight 2D lines are interpreted as straight 3D lines;

- 2D parallel lines are interpreted as 3D parallel lines;

- acute and obtuse angles are interpreted as right angles in perspective;

- the outer lines are considered as the boundary of the form. This outer boundary is extremely important for constructing a complete image.

Human consciousness first creates a general image of an object, and then examines individual parts. Each angle is compatible with spatial perspective, but when reunited they form a spatial paradox. If you close any of the corners of the triangle, then the impossibility disappears.

History of impossible figures

Errors in spatial construction were encountered by artists even a thousand years ago. But the first to construct and analyze impossible objects is considered to be the Swedish artist Oscar Reutersvard, who in 1934 drew the first impossible triangle, consisting of nine cubes.

Independent of Reuters, English mathematician and physicist Roger Penrose rediscovers the impossible triangle and publishes an image of it in a British psychology journal in 1958. The illusion uses “false perspective.” Sometimes this perspective is called Chinese, since a similar method of drawing, when the depth of the drawing is “ambiguous,” was often found in the works of Chinese artists.

|

| Impossible cube |

In 1961, the Dutchman Maurits C. Escher, inspired by the impossible Penrose triangle, created the famous lithograph “Waterfall”. The water in the picture flows endlessly, after the water wheel it passes further and ends up back at the starting point. In essence, this is an image of a perpetual motion machine, but any attempt to actually build this structure is doomed to failure.

Since then, the impossible triangle has been used more than once in the works of other masters. In addition to those already mentioned, we can name the Belgian Jos de Mey, the Swiss Sandro del Prete and the Hungarian Istvan Orosz.

Images are formed both from individual pixels on the screen and from the main geometric shapes you can create objects of impossible reality. For example, the drawing “Moscow”, which depicts an unusual diagram of the Moscow metro. At first we perceive the image as a whole, but when we trace the individual lines with our gaze, we become convinced of the impossibility of their existence.

In the "Three Snails" drawing, the small and large cubes are not oriented in a normal isometric projection. The smaller cube is adjacent to the larger one on the front and back sides, which means, following three-dimensional logic, it has the same dimensions of some sides as the larger one. At first the drawing seems like a real representation solid, but as the analysis proceeds, logical contradictions of this object are revealed.

The “Three Snails” drawing continues the tradition of the second famous impossible figure - the impossible cube (box).

A combination of various objects can also be found in the not entirely serious drawing “IQ” (intelligence quotient). Interestingly, some people do not perceive impossible objects because their minds are unable to identify flat pictures with three-dimensional objects.

Donald E. Simanek has suggested that understanding visual paradoxes is one of the hallmarks of the kind of creativity that the best mathematicians, scientists and artists possess. Many works with paradoxical objects can be classified as “intellectual mathematical games”. Modern science speaks of a 7-dimensional or 26-dimensional model of the world. Such a world can only be modeled using mathematical formulas; humans simply cannot imagine it. This is where impossible figures come in handy. WITH philosophical point vision, they serve as a reminder that any phenomena (in system analysis, science, politics, economics, etc.) should be considered in all complex and non-obvious relationships.

A variety of impossible (and possible) objects are presented in the painting “Impossible Alphabet.”

A third popular impossible figure is the incredible staircase created by Penrose. You will continuously either ascend (counterclockwise) or descend (clockwise) along it. The Penrose model formed the basis famous painting M. Escher “Up and Down” (“Ascending and Descending”).

There is another group of objects that cannot be implemented. The classic figure is the impossible trident, or "devil's fork".

If you carefully study the picture, you will notice that three teeth gradually turn into two on a single base, which leads to a conflict. We compare the number of teeth above and below and come to the conclusion that the object is impossible.

Internet resources about impossible objects

The impossible is what

that cannot exist...

or happen...

The purpose of the lesson: development of three-dimensional vision of students; the ability to explain the impossibility of the existence of a particular figure from the point of view of geometry; development of interest in the subject.

Equipment: newspaper based on materials from the site " Impossible world" (Internet), tools for constructing figures, geometric figures, illustrations of impossible figures.

During the classes:

Introduction:

Throughout history, people have encountered optical illusions of one kind or another. Suffice it to recall the mirage in the desert, illusions created by light and shadow, as well as relative movement. The following example is widely known: the moon rising from the horizon appears much larger than it is high in the sky. All these are just a few interesting phenomena that occur in nature. When these phenomena, which deceive the eyes and the mind, were first noticed, they began to excite the imagination of people.

Since ancient times, optical illusions have been used to enhance the impact of works of art or improve appearance architectural creations. The ancient Greeks used optical illusions to perfect the appearance of their great temples. During the Middle Ages, shifted perspective was sometimes used in painting. Later, many other illusions were used in graphics. Among them is the only one of its kind and a relatively new species optical illusion known as "impossible objects".

One of the important skills for people working in technical fields is the ability to perceive three-dimensional objects in a two-dimensional plane. "Impossible Objects" is built on the use of tricks with perspective and depth within two-dimensional space. Impossible in real three-dimensional space, they affect our vision through displaced perspective, manipulation of depth and plane, deceptive optical cues, inconsistencies in plans, play of light and shadow, unclear connections, due to incorrect and contradictory directions and connections, altered code points and others. "tricks" that the graphic artist resorts to.

The deliberate use of impossible objects in design dates back to ancient times before the advent of classical perspective. Artists tried to find new solutions. An example is the 15th-century depiction of the Annunciation on the fresco of St. Mary's Cathedral in the Dutch city of Breda. The painting depicts the Archangel Gabriel bringing Mary the news of her future Son. The fresco is framed by two arches, supported in turn by three columns. However, you should pay attention to the middle column. Unlike the others, she disappears into the background behind the stove. From a practical point of view, the artist used this "impossibility" as a special technique to avoid dividing the scene into two halves.

An example of such an arch is shown in Fig. 1

"Impossible figures" are divided into 4 groups. Let's now try to sort out the main figures from each group. So, the first one:

Student 1:

An amazing triangle - tribar.

This figure is perhaps the first impossible object published in print. It appeared in 1958. Its authors, father and son Lionell and Roger Penrose, a geneticist and mathematician respectively, defined the object as a "three-dimensional rectangular structure." It was also called "tribar".

Determine what is geometrically impossible.

(At first glance, the tribar appears to be simply an image of an equilateral triangle. But the sides converging at the top of the picture appear perpendicular. At the same time, the left and right edges below also appear perpendicular. If you look at each detail separately, it seems real, but in general this figure cannot exist. It is not deformed, but the correct elements were incorrectly connected when drawing.)

Here are some more examples of impossible figures based on the tribar. Try to explain their impossibility.

Triple warped tribar

Triangle of 12 cubes

Winged Tribar

Triple domino

Student 2:

Endless staircase

This figure is most often called the “Endless Staircase”, “Eternal Staircase” or “Penrose Staircase” - after its creator. It is also called the "continuously ascending and descending path."

This figure was first published in 1958. A staircase appears before us, seemingly leading up or down, but at the same time, the person walking along it does not rise or fall. Having completed his visual route, he will find himself at the beginning of the path.

The “Endless Staircase” was successfully used by the artist Maurits K. Escher, this time in his lithograph “Ascent and Descend”, created in 1960.

Staircase with four or seven steps.

The creation of this figure with a large number of steps could have been inspired by a pile of ordinary railroad sleepers. When you are about to climb this ladder, you will be faced with a choice: whether to climb four or seven steps.

Try to explain what properties the creators of this staircase used.

(The creators of this staircase took advantage of parallel lines to design the end pieces of the equally spaced blocks; some blocks appear to be twisted to fit the illusion).

It is suggested to look at one more figure. Step wall.

Student 3:

The next group of figures is collectively called the “Space Fork”. With this figure we enter into the very core and essence of the impossible. This may be the largest class of impossible objects.

This notorious impossible object with three (or two?) teeth became popular with engineers and puzzle enthusiasts in 1964. The first publication dedicated to the unusual figure appeared in December 1964. The author called it a “Brace consisting of three elements.” Perceiving and resolving (if possible) the inconsistency in this new type of ambiguous figure requires a real shift in visual fixation. From a practical point of view, this strange trident or bracket-like mechanism is absolutely inapplicable. Some simply call it an "unfortunate mistake." One of the representatives of the aerospace industry proposed using its properties in the construction of an interdimensional space tuning fork.

Tower with four twin columns.

Student 4:

Another impossible object appeared in 1966 in Chicago as a result of original experiments by photographer Dr. Charles F. Cochran. Many lovers of impossible figures have experimented with the Crazy Box. The author originally called it the "Free Box" and stated that it was "designed to send impossible objects in large numbers."

The “crazy box” is the frame of a cube turned inside out. The immediate predecessor of the Crazy Box was the Impossible Box (by Escher), and its predecessor in turn was the Necker Cube.

It is not an impossible object, but it is a figure in which the depth parameter can be perceived ambiguously.

The Necker cube was first described in 1832 by Swiss crystallographer Lewis A. Necker, who noticed that crystals sometimes visually change shape when you look at them. When we look at the Necker cube, we notice that the face with the dot is either in the foreground or in the background, it jumps from one position to another.

A few more impossible figures.

Teacher:

Now try to create some impossible figure yourself.

The lesson ends with students trying to draw an impossible figure on their own.

Impossible figures

- special kind objects in fine art. Typically they are called that because they cannot exist in the real world.

More precisely, impossible figures are geometric objects drawn on paper that give the impression of an ordinary projection of a three-dimensional object, however, upon careful examination, contradictions in the connections of the elements of the figure become visible.

Impossible figures are classified as a separate class of optical illusions.

Impossible constructions have been known since ancient times. They have been found in icons since the Middle Ages. A Swedish artist is considered the “father” of impossible figures Oscar Reutersvard, who drew an impossible triangle made from cubes in 1934.

Impossible figures became known to the general public in the 50s of the last century, after the publication of an article by Roger Penrose and Lionel Penrose, in which two were described basic figures- impossible triangle (also called trianglePenrose) and an endless staircase. This article came into the hands of a famous Dutch artistM.K. Escher, who, inspired by the idea of impossible figures, created his famous lithographs "Waterfall", "Ascent and Descent" and "Belvedere". Following him great amount Artists around the world began to use impossible figures in their work. The most famous among them are Jos de Mey, Sandro del Pre, Ostvan Oros. The works of these, as well as other artists, are distinguished into a separate direction visual arts - "

imp-art"

.

It may seem that impossible figures really cannot exist in three-dimensional space. There are certain ways that you can reproduce impossible figures in the real world, although they will only look impossible from one vantage point.

The most famous impossible figures are: the impossible triangle, the infinite staircase and the impossible trident.

Article from the journal Science and Life "Impossible Reality"

download

Oscar Ruthersward(the spelling of the surname customary in Russian-language literature; more correctly Reuterswerd), ( 1

915 - 2002) is a Swedish artist who specialized in depicting impossible figures, that is, those that can be depicted, but cannot be created. One of his figures received further development like the Penrose triangle.

Since 1964, professor of history and art theory at Lund University.

Rutersvard was greatly influenced by the lessons of the Russian immigrant, professor at the Academy of Arts in St. Petersburg, Mikhail Katz. He created the first impossible figure - an impossible triangle made from a set of cubes - by accident in 1934. Later, over the years of creativity, he drew more than 2,500 different impossible figures. All of them are made in a parallel “Japanese” perspective.

In 1980, the Swedish government released a series of three postage stamps with paintings by the artist.

Impossible figures are figures depicted in perspective in such a way as to appear at first glance to be an ordinary figure. However, upon closer examination, the viewer realizes that such a figure cannot exist in three-dimensional space. Escher depicted impossible figures in his famous paintings Belvedere (1958), Ascent and Descend (1960) and Waterfall (1961). One example of an impossible figure is a painting by the contemporary Hungarian artist Istvan Orosz.

Istvan Oros "Crossroads" (1999). Reproduction of metal engraving. The painting depicts bridges that cannot exist in three-dimensional space. For example, there are reflections in the water that cannot be the original bridges.

the Mobius strip

A Möbius strip is a three-dimensional object that has only one side. This type of tape can easily be made from a strip of paper by twisting one end of the strip and then gluing both ends together. Escher depicted the Möbius strip in Riders (1946), Möbius Strip II (Red Ants) (1963) and Knots (1965).

“Knots” - Maurits Cornelis Escher 1965

Later, minimum energy surfaces became an inspiration for many mathematical artists. Brent Collins, uses Möbius strips and minimum energy surfaces, as well as other types of abstractions in sculpture.

Distorted and unusual perspectives

Unusual perspective systems containing two or three vanishing points are also a favorite theme of many artists. These also include a related field - anamorphic art. Escher used distorted perspective in several of his works, Above and Below (1947), House of Stairs (1951), and The Picture Gallery (1956). Dick Termes uses six-point perspective to draw scenes on spheres and polyhedra, as shown in the example below.

Dick Termes "A Cage for Man" (1978). This is a painted sphere that was created using six-point perspective. It depicts a geometric structure in the form of a grid, through which the landscape is visible. Three branches penetrate into the cage, and reptiles crawl along it. While some explore the world, others find themselves caged.

The word anamorphic is formed from two Greek words "ana" (again) and morthe (form). Anamorphic images are images that are so severely distorted that it can be impossible to make them out without a special mirror. This mirror is sometimes called an anamorphoscope. If you look through an anamorphoscope, the image “forms again” into a recognizable picture. European artists early renaissance were fascinated by linear anamorphic paintings, where an elongated picture became normal again when viewed at an angle. A famous example is Hans Holbein's painting "The Ambassadors" (1533), which depicts an elongated skull. The painting can be tilted at the top of the stairs so that people walking up the stairs will be startled by the image of the skull. Anamorphic paintings, which require cylindrical mirrors to view, were popular in Europe and the East in XVII-XVIII centuries. Often such images carried messages of political protest or were of erotic content. Escher did not use classic anamorphic mirrors in his work, however, he did use spherical mirrors in some of his paintings. His most famous work in this style is “Hand with a Reflecting Sphere” (1935). The example below shows a classic anamorphic image by Istvan Orosz.

Istvan Oros "The Well" (1998). The painting "Well" was printed from a metal engraving. The work was created for the centenary of the birth of M.K. Escher. Escher wrote about excursions into mathematical art as being like walking through a beautiful garden where nothing is repeated. The gate on the left side of the picture separates Escher's mathematical garden, located in the brain, from physical world. The broken mirror on the right side of the painting shows a view of the small town of Atrani on the Amalfi Coast in Italy. Escher loved the place and lived there for some time. He depicted this city in the second and third paintings from the Metamorphoses series. If you place a cylindrical mirror in place of the well, as shown on the right, Escher's face will appear in it, as if by magic.